Asterix

| Asterix (Astérix le Gaulois) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Publication information | |||

| Publisher | Dargaud, Éditions Albert René, Hachette for canonical volumes in French; others for non-canonical volumes (1976–1996) in French; Hodder, Hachette and others for non-canonical volumes (1976–1996) in English | ||

| |||

| Formats | Original material for the series has been published as a strip in the comics anthology(s) Pilote. | ||

| Genre | |||

| Publication date | 29 October 1959 – present (original); 1969–present (English translation) | ||

| Creative team | |||

| Writer(s) |

| ||

| Artist(s) |

| ||

| Translators |

| ||

Asterix (Astérix or Astérix le Gaulois [asteʁiks lə ɡolwa], "Asterix the Gaul") (also known as Asterix and Obelix in some adaptations or The Adventures of Asterix) is a French comic album series about a village of indomitable Gaulish warriors (including the titular hero Asterix) who adventure around the world and fight the odds of the Roman Republic. This is done with the aid of a magic potion, during the era of Julius Caesar in an ahistorical telling of the time after the Gallic Wars.

The series first appeared in the Franco-Belgian comic magazine Pilote on 29 October 1959. It was written by René Goscinny and illustrated by Albert Uderzo until Goscinny's death in 1977. Uderzo then took over the writing until 2009, when he sold the rights to publishing company Hachette; he died in 2020. In 2013, a new team consisting of Jean-Yves Ferri (script) and Didier Conrad (artwork) took over. As of 2023[update], 40 volumes have been released; the most recent was penned by new writer Fabcaro and released on 26 October 2023.

By that year, the volumes in total had sold 393 million copies,[1] making them the best-selling European comic book series, and the second best-selling comic book series in history after One Piece.

Description

[edit]

Asterix comics usually start with the following introduction:

The year is 50 BC. Gaul is entirely occupied by the Romans. Well, not entirely... One small village of indomitable Gauls still holds out against the invaders. And life is not easy for the Roman legionaries who garrison the fortified camps of Totorum, Aquarium, Laudanum and Compendium...[2][3]

The series follows the adventures of a village of Gauls as they resist Roman occupation in 50 BC. They do so using a magic potion, brewed by their druid Getafix (Panoramix in the French version), which temporarily gives the recipient superhuman strength. The protagonists, the title character Asterix and his friend Obelix, have various adventures. The "-ix" ending of both names (as well as all the other pseudo-Gaulish "-ix" names in the series) alludes to the "-rix" suffix (meaning "king", like "-rex" in Latin) present in the names of many real Gaulish chieftains such as Vercingetorix, Orgetorix, and Dumnorix.

In some of the stories, they travel to foreign countries, whilst other tales are set in and around their village. For much of the history of the series (volumes 4 through 29), settings in Gaul and abroad alternate, with even-numbered volumes set abroad and odd-numbered volumes set in Gaul, mostly in the village.

The Asterix series is one of the most popular Franco-Belgian comics in the world, with the series being translated into 111 languages and dialects as of 2009[update].[4]

The success of the series has led to the adaptation of its books into 15 films: ten animated, and five live action (two of which, Asterix & Obelix: Mission Cleopatra and Asterix and Obelix vs. Caesar, were major box office successes in France). There have also been a number of games based on the characters, and a theme park near Paris, Parc Astérix. The very first French satellite, Astérix, launched in 1965, was named after the character, whose name is close to Greek ἀστήρ and Latin astrum, meaning a "star". As of 20 April 2022, 385 million copies of Asterix books had been sold worldwide and translated in 111 languages making it the world's most widely translated comic book series,[5] with co-creators René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo being France's best-selling authors abroad.[6][7]

In April 2022, Albert and René's general director, Céleste Surugue, hosted a 45-minute talk entitled 'The Next Incarnation of a Heritage Franchise: Asterix' and spoke about the success of the Asterix franchise, of which he noted "The idea was to find a subject with a strong connection with French culture and, while looking at the country's history, they ended up choosing its first defeat, namely the Gaul's Roman colonisation". He also went on to say how, since 1989, Parc Asterix has attracted an average of 2.3 million visitors per year. Other notable mentions were how the franchise includes 10 animated movies, which recorded over 53 million viewers worldwide. The inception of Studios Idéfix in 1974 and the opening of Studio 58 in 2016 were among the necessary steps to make Asterix a "100% Gaulish production", considered the best solution to keep the creative process under control from start to finish and to employ French manpower. He also noted how a new album is now published every two years, with print figures of 5 million and an estimated readership of 20 million.[5]

Publication history

[edit]

Prior to creating the Asterix series, Goscinny and Uderzo had had success with their series Oumpah-pah, which was published in Tintin magazine.[9] Astérix was originally serialised in Pilote magazine, debuting in the first issue on 29 October 1959.[10] In 1961, the first book was put together, titled Asterix the Gaul. From then on, books were released generally on a yearly basis. Their success was exponential; the first book sold 6,000 copies in its year of publication; a year later, the second sold 20,000. In 1963, the third sold 40,000; the fourth, released in 1964, sold 150,000. A year later, the fifth sold 300,000; 1966's Asterix and the Big Fight sold 400,000 upon initial publication. The ninth Asterix volume, when first released in 1967, sold 1.2 million copies in two days.

Uderzo's first preliminary sketches portrayed Asterix as a huge and strong traditional Gaulish warrior. But Goscinny had a different picture in his mind, visualizing Asterix as a shrewd, compact warrior who would possess intelligence and wit more than raw strength. However, Uderzo felt that the downsized hero needed a strong but dim companion, to which Goscinny agreed. Hence, Obelix was born.[11] Despite the growing popularity of Asterix with the readers, the financial backing for the publication Pilote ceased. Pilote was taken over by Georges Dargaud.[11]

When Goscinny died in 1977, Uderzo continued the series by popular demand of the readers, who implored him to continue. He continued to issue new volumes of the series, but on a less frequent basis. Many critics and fans of the series prefer the earlier collaborations with Goscinny.[12] Uderzo created his own publishing company, Éditions Albert René, which published every album drawn and written by Uderzo alone since then.[11] However, Dargaud, the initial publisher of the series, kept the publishing rights on the 24 first albums made by both Uderzo and Goscinny. In 1990, the Uderzo and Goscinny families decided to sue Dargaud to take over the rights. In 1998, after a long trial, Dargaud lost the rights to publish and sell the albums. Uderzo decided to sell these rights to Hachette instead of Albert-René, but the publishing rights on new albums were still owned by Albert Uderzo (40%), Sylvie Uderzo (20%) and Anne Goscinny (40%).[citation needed]

In December 2008, Uderzo sold his stake to Hachette, which took over the company.[13] In a letter published in the French newspaper Le Monde in 2009, Uderzo's daughter, Sylvie, attacked her father's decision to sell the family publishing firm and the rights to produce new Astérix adventures after his death. She said:

... the co-creator of Astérix, France's comic strip hero, has betrayed the Gaulish warrior to the modern-day Romans – the men of industry and finance.[14][15]

However, René Goscinny's daughter, Anne, also gave her agreement to the continuation of the series and sold her rights at the same time. She is reported to have said that "Asterix has already had two lives: one during my father's lifetime and one after it. Why not a third?".[16] A few months later, Uderzo appointed three illustrators, who had been his assistants for many years, to continue the series.[12] In 2011, Uderzo announced that a new Asterix album was due out in 2013, with Jean-Yves Ferri writing the story and Frédéric Mébarki drawing it.[17] A year later, in 2012, the publisher Albert-René announced that Frédéric Mébarki had withdrawn from drawing the new album, due to the pressure he felt in following in the steps of Uderzo. Comic artist Didier Conrad was officially announced to take over drawing duties from Mébarki, with the due date of the new album in 2013 unchanged.[18][19]

In January 2015, after the murders of seven cartoonists at the satirical Paris weekly Charlie Hebdo, Astérix creator Albert Uderzo came out of retirement to draw two Astérix pictures honouring the memories of the victims.[20]

List of titles

[edit]Numbers 1–24, 32 and 34 are by Goscinny and Uderzo. Numbers 25–31 and 33 are by Uderzo alone. Numbers 35–39 are by Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad. Years stated are for their initial album release.[21]

- Asterix the Gaul (1961)[22][23]

- Asterix and the Golden Sickle (1962)[22][24]

- Asterix and the Goths (1963)[22][25]

- Asterix the Gladiator (1964)[22][26]

- Asterix and the Banquet (1965)[22][27]

- Asterix and Cleopatra (1965)[22][28]

- Asterix and the Big Fight (1966)[22][29]

- Asterix in Britain (1966)[22][30]

- Asterix and the Normans (1967)[22][31]

- Asterix the Legionary (1967)[22][32]

- Asterix and the Chieftain's Shield (1967)[22][33]

- Asterix at the Olympic Games (1968)[22][34]

- Asterix and the Cauldron (1969)[22][35]

- Asterix in Spain (1969)[22][36]

- Asterix and the Roman Agent (1970)[22][37]

- Asterix in Switzerland (1970)[22][38]

- The Mansions of the Gods (1971)[22][39]

- Asterix and the Laurel Wreath (1972)[22][40]

- Asterix and the Soothsayer (1972)[22][41]

- Asterix in Corsica (1973)[22][42]

- Asterix and Caesar's Gift (1974)[22][43]

- Asterix and the Great Crossing (1975)[22][44]

- Obelix and Co. (1976)[22][45]

- Asterix in Belgium (1979)[22][46]

- Asterix and the Great Divide (1980)[22][47]

- Asterix and the Black Gold (1981)[22][48]

- Asterix and Son (1983)[22][49]

- Asterix and the Magic Carpet (1987)[22][50]

- Asterix and the Secret Weapon (1991)[22][51]

- Asterix and Obelix All at Sea (1996)[52]

- Asterix and the Actress (2001)[53]

- Asterix and the Class Act (2003)[54]

- Asterix and the Falling Sky (2005)[55]

- Asterix and Obelix's Birthday: The Golden Book (2009)[56][57]

- Asterix and the Picts (2013)[58]

- Asterix and the Missing Scroll (2015)[59]

- Asterix and the Chariot Race (2017)[60]

- Asterix and the Chieftain's Daughter (2019)[61]

- Asterix and the Griffin (2021)[62]

- Asterix and the White Iris (2023)[63]

- Non-canonical volumes:

- Asterix Conquers Rome, to be the 23rd volume, before Obelix and Co. (1976) – comic

- How Obelix Fell into the Magic Potion When he was a Little Boy (1989) – special issue album

- Uderzo Croqué par ses Amis (Uderzo sketched by his friends) (1996) – tribute album by various artists

- The Twelve Tasks of Asterix (2016)[64] – special issue album, illustrated text

Asterix Conquers Rome is a comics adaptation of the animated film The Twelve Tasks of Asterix. It was released in 1976 and was the 23rd volume to be published, but it has been rarely reprinted and is not considered to be canonical to the series. The only English translations ever to be published were in the Asterix Annual 1980 and never an English standalone volume. A picture-book version of the same story was published in English translation as The Twelve Tasks of Asterix by Hodder & Stoughton in 1978.

In 1996, a tribute album in honour of Albert Uderzo was released titled Uderzo Croqué par ses Amis, a volume containing 21 short stories with Uderzo in Ancient Gaul. This volume was published by Soleil Productions and has not been translated into English.

In 2007, Éditions Albert René released a tribute volume titled Astérix et ses Amis, a 60-page volume of one-to-four-page short stories. It was a tribute to Albert Uderzo on his 80th birthday by 34 European cartoonists. The volume was translated into nine languages. As of 2016[update], it has not been translated into English.[65]

In 2016, the French publisher Hachette, along with Anne Goscinny and Albert Uderzo decided to make the special issue album The XII Tasks of Asterix for the 40th anniversary of the film The Twelve Tasks of Asterix. There was no English edition.

Synopsis and characters

[edit]The main setting for the series is an unnamed coastal village, rumoured to be inspired by Erquy[66] in Armorica (present-day Brittany), a province of Gaul (modern France), in the year 50 BC. Julius Caesar has conquered nearly all of Gaul for the Roman Empire during the Gallic Wars. The little Armorican village, however, has held out because the villagers can gain temporary superhuman strength by drinking a magic potion brewed by the local village druid, Getafix. His chief is Vitalstatistix.

The main protagonist and hero of the village is Asterix, who, because of his shrewdness, is usually entrusted with the most important affairs of the village. He is aided in his adventures by his rather corpulent and slower thinking friend, Obelix, who, because he fell into the druid's cauldron of the potion as a baby, has permanent superhuman strength (because of this, Getafix steadfastly refuses to allow Obelix to drink the potion, as doing so would have a dangerous and unpredictable result, as shown in Asterix and Obelix All at Sea). Obelix is usually accompanied by Dogmatix, his little dog. (Except for Asterix and Obelix, the names of the characters change with the language. For example, Obelix's dog's name is "Idéfix" in the original French edition.)

Asterix and Obelix (and sometimes other members of the village) go on various adventures both within the village and in far away lands. Places visited in the series include parts of Gaul (Lutetia, Corsica etc.), neighbouring nations (Belgium, Spain, Britain, Germany etc.), and far away lands (North America, Middle East, India etc.).

The series employs science-fiction and fantasy elements in the more recent books; for instance, the use of extraterrestrials in Asterix and the Falling Sky and the city of Atlantis in Asterix and Obelix All at Sea.

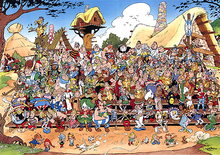

With rare exceptions, the ending of the albums usually shows a big banquet with the village's inhabitants gathering – the sole exception is the bard Cacofonix restrained and gagged to prevent him from singing (but in Asterix and the Normans the blacksmith Fulliautomatix was tied up). Mostly the banquets are held under the starry nights in the village, where roast boar is devoured and all (but one) are set about in merrymaking. However, there are a few exceptions, such as in Asterix and Cleopatra.

Humour

[edit]The humour encountered in the Asterix comics often centers around puns, caricatures, and tongue-in-cheek stereotypes of contemporary European nations and French regions. Much of the multi-layered humour in the initial Asterix books was French-specific, which delayed the translation of the books into other languages for fear of losing the jokes and the spirit of the story. Some translations have actually added local humour: In the Italian translation, the Roman legionaries are made to speak in 20th-century Roman dialect, and Obelix's famous Ils sont fous, ces Romains ("These Romans are crazy") is translated properly as Sono pazzi questi romani, humorously alluding to the Roman abbreviation SPQR. In another example: Hiccups are written onomatopoeically in French as hips, but in English as "hic", allowing Roman legionaries in more than one of the English translations to decline their hiccups absurdly in Latin (hic, haec, hoc). The newer albums share a more universal humour, both written and visual.[67]

Character names

[edit]All the fictional characters in Asterix have names which are puns on their roles or personalities, and which follow certain patterns specific to nationality. Certain rules are followed (most of the time) such as Gauls (and their neighbours) having an "-ix" suffix for the men and ending in "-a" for the women; for example, Chief Vitalstatistix (so called due to his portly stature) and his wife Impedimenta (often at odds with the chief). The male Roman names end in "-us", echoing Latin nominative male singular form, as in Gluteus Maximus, a muscle-bound athlete whose name is literally the butt of the joke. Gothic names (present-day Germany) end in "-ic", after Gothic chiefs such as Alaric and Theoderic; for example Rhetoric the interpreter. Greek names end in "-os" or "-es"; for example, Thermos the restaurateur. British names usually end in "-ax" or "-os" and are often puns on the taxation associated with the later United Kingdom; examples include Mykingdomforanos, a British tribal chieftain, Valuaddedtax the druid, and Selectivemploymentax the mercenary. Names of Normans end with "-af", for example Nescaf or Cenotaf. Egyptian characters often end in -is, such as the architects Edifis and Artifis, and the scribe Exlibris. Indic names, apart from the only Indic female characters Orinjade and Lemuhnade, exhibit considerable variation; examples include Watziznehm, Watzit, Owzat, and Howdoo. Other nationalities are treated to pidgin translations from their language, like Huevos y Bacon, a Spanish chieftain (whose name, meaning eggs and bacon, is often guidebook Spanish for tourists), or literary and other popular media references, like Dubbelosix (a sly reference to James Bond's codename "007").[68]

Most of these jokes, and hence the names of the characters, are specific to the translation; for example, the druid named Getafix in English translation – "get a fix", referring to the character's role in dispensing the magic potion – is Panoramix in the original French and Miraculix in German.[69] Even so, occasionally the wordplay has been preserved: Obelix's dog, known in the original French as Idéfix (from idée fixe, a "fixed idea" or obsession), is called Dogmatix in English, which not only renders the original meaning strikingly closely ("dogmatic") but in fact adds another layer of wordplay with the syllable "Dog-" at the beginning of the name.

The name Asterix, French Astérix, comes from astérisque, meaning "asterisk", which is the typographical symbol * indicating a footnote, from the Greek word ἀστήρ (aster), meaning a "star". His name is usually left unchanged in translations, aside from accents and the use of local alphabets. For example, in Esperanto, Polish, Slovene, Latvian, and Turkish it is Asteriks (in Turkish he was first named Bücür meaning "shorty", but the name was then standardised). Two exceptions include Icelandic, in which he is known as Ástríkur ("Rich of love"), and Sinhala, where he is known as සූර පප්පා (Soora Pappa), which can be interpreted as "Hero". The name Obelix (Obélix) may refer to "obelisk", a stone column from ancient Egypt (and hence his large size and strength and his task of carrying around menhirs), but also to another typographical symbol, the obelisk or obelus (†).

For explanations of some of the other names, see List of Asterix characters.

Ethnic stereotypes

[edit]Many of the Asterix adventures take place in other countries away from their homeland in Gaul. In every album that takes place abroad, the characters meet (usually modern-day) stereotypes for each country, as seen by the French.[70]

- Italics (Italians) are the inhabitants of Italy. In the adventures of Asterix, the term "Romans" is used by non-Italics to refer to all inhabitants of Italy, who at that time had extended their dominion over a large part of the Mediterranean basin. But as can be seen in Asterix and the Chariot Race, in the Italian Peninsula this term is used only to refer to the people from the capital, with many Italics preferring to identify themselves as Umbrians, Etruscans, Venetians, etc. Various topics from this country are explored, as in this example, Italian cuisine (pasta, pizza, wine), art, famous people (Luciano Pavarotti, Silvio Berlusconi, Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa), and even the controversial issues of political corruption. Romans in general appear more similar to the historical Romans than to modern-age Italians.

- Goths (Germans) are disciplined and militaristic, but divided into many factions that fight amongst each other (which is a reference to Germany before Otto von Bismarck, and to the rivalry between East Germany and West Germany in the Aftermath of World War II), and they wear the Pickelhaube helmet common during the German Empire. In later appearances, the Goths tend to be more good-natured.

- Helvetians (Swiss) are neutral, eat fondue, and are obsessed with cleaning, accurate time-keeping, and banks.

- The Britons (English) are phlegmatic, and speak with early 20th-century aristocratic slang (similar to Bertie Wooster). They stop for tea every day (making it with hot water and a drop of milk until Asterix brings them actual tea leaves), drink lukewarm beer (Bitter), eat tasteless foods with mint sauce (Rosbif), and live in streets containing rows of identical houses. In Asterix and Obelix: God Save Britannia the Britons all wore woollen pullovers and Tam o' shanters.

- Hibernians (Irish) inhabit Hibernia, the Latin name of Ireland and they fight against the Romans alongside the Britons to defend the British Isles.

- Iberians (Spanish) are filled with pride and have rather choleric tempers. They produce olive oil, provide very slow aid for chariot problems on the Roman roads and (thanks to Asterix) adopt bullfighting as a tradition.

- When the Gauls visited North America in Asterix and the Great Crossing, Obelix punches one of the attacking Native Americans with a knockout blow. The warrior first hallucinates American-style emblematic eagles; the second time, he sees stars in the formation of the Stars and Stripes; the third time, he sees stars shaped like the United States Air Force roundel. Asterix's inspired idea for getting the attention of a nearby Viking ship (which could take them back to Gaul) is to hold up a torch; this refers to the Statue of Liberty (which was a gift from France).

- Corsicans are proud, patriotic, and easily aroused but lazy, making decisions by using pre-filled ballot boxes. They harbour vendettas against each other, and always take their siesta.

- Greeks are chauvinists and consider Romans, Gauls, and all others to be barbarians. They eat stuffed grape leaves (dolma), drink resinated wine (retsina), and are hospitable to tourists. Most seem to be related by blood, and often suggest some cousin appropriate for a job. Greek characters are often depicted in side profile, making them resemble figures from classical Greek vase paintings.

- Normans (Vikings) drink endlessly, they always use cream in their cuisine, they don't know what fear is (which they're trying to discover), and in their home territory (Scandinavia), the night lasts for 6 months.

Their depiction in the albums is a mix of stereotypes of Scandinavian Vikings and the Norman French. - Cimbres (Danes) are very similar to the Normans with the greatest difference being that the Gauls are unable to communicate with them. Their names end in "-sen", a common ending of surnames in Denmark and Norway akin to "-son".

- Belgians speak with a funny accent, snub the Gauls, and always eat sliced roots deep-fried in bear fat. They also tell Belgian jokes.

- Lusitanians (Portuguese) are short in stature and polite (Uderzo said all the Portuguese who he had met were like that).

- The Indians have elephant trainers, as well as gurus who can fast for weeks and levitate on magic carpets. They worship thirty-three million deities and consider cows as sacred. They also bathe in the Ganges river.

- Egyptians are short with prominent noses, endlessly engaged in building pyramids and palaces. Their favorite food is lentil soup and they sail feluccas along the banks of the Nile River.

- Persians (Iranians) produce carpets and staunchly refuse to mend foreign ones. They eat caviar, as well as roasted camel and the women wear burqas.

- Hittites, Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians, and Babylonians are perpetually at war with each other and attack strangers because they confuse them with their enemies, but they later apologize when they realize that the strangers are not their enemies. This is likely a criticism of the constant conflicts among the Middle Eastern peoples.

- The Jews are all depicted as Yemenite Jews, with dark skin, black eyes, and beards, a tribute to Marc Chagall, the famous painter whose painting of King David hangs at the Knesset (Israeli Parliament).

- Numidians, contrary to the Berber inhabitants of ancient Numidia (located in North Africa), are obviously Africans from sub-Saharan Africa. The names end in "-tha", similar to the historical king Jugurtha of Numidia.

- The Picts (Scots) wear a typical dress with a kilt (skirt), have the habit of drinking "malt water" (whisky) and throwing logs (caber tossing) as a popular sport and their names all start with "Mac-".

- Sarmatians (Ukrainians) inhabit the North Black Sea area, which represents present-day Ukraine. Their names end in "-ov", like many Ukrainian surnames.

When the Gauls see foreigners speaking their foreign languages, these have different representations in the cartoon speech bubbles:

- Iberian: Same as Spanish, with inversion of exclamation marks ('¡') and question marks ("¿")

- Goth language: Gothic script (incomprehensible to the Gauls, except Getafix, who speaks Gothic)

- Viking (Normans and Cimbres): "Ø" and "Å" instead of "O" and "A" (incomprehensible to the Gauls)

- Amerindian: Pictograms and sign language (generally incomprehensible to the Gauls)

- Egyptians and Kushites: Hieroglyphs with explanatory footnotes (incomprehensible to the Gauls)

- Greek: Straight letters, carved as if in stone

- Sarmatian: In their speech balloons, some letters (E, F, N, R ...) are written in a mirror-reversed form, which evokes the modern Cyrillic alphabet.

Translations

[edit]The various volumes have been translated into more than 120 languages and dialects. Besides the original French language, most albums are available in Arabic, Basque, Bulgarian, Catalan, Chinese, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Finnish, Galician, German, Greek, Hebrew, Hindi, Icelandic, Irish, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Latin, Latvian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovene, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Ukrainian.[71][72]

Some books have also been translated into languages including Esperanto, Scottish Gaelic, Irish, Scots, Indonesian, Hindi, Persian, Bengali, Afrikaans, Arabic, Frisian, Romansch, Thai, Vietnamese, Welsh, Sinhala, Ancient Greek, and Luxembourgish.[71]

In Europe, several volumes were translated into a variety of regional languages and dialects, such as Alsatian, Breton, Chtimi (Picard), and Corsican in France; Bavarian, Swabian, and Low German in Germany; and Savo, Karelia, Rauma, and Helsinki slang dialects in Finland. In Portugal a special edition of the first volume, Asterix the Gaul, was translated into local language Mirandese.[73] In Greece, a number of volumes have appeared in the Cretan Greek, Cypriot Greek, and Pontic Greek dialects.[74] In the Italian version, while the Gauls speak standard Italian, the legionaries speak in the Romanesque dialect. In the former Yugoslavia, the "Forum" publishing house translated Corsican text in Asterix in Corsica into the Montenegrin dialect of Serbo-Croatian (today called Montenegrin).

In the Netherlands, several volumes were translated into West Frisian, a Germanic language spoken in the province of Friesland; into Limburgish, a regional language spoken not only in Dutch Limburg but also in Belgian Limburg and North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany; and into Tweants, a dialect in the region of Twente in the eastern province of Overijssel. Hungarian-language books were published in the former Yugoslavia for the Hungarian minority living in Serbia. Although not translated into a fully autonomous dialect, the books differ slightly from the language of the books issued in Hungary. In Sri Lanka, the cartoon series was adapted into Sinhala as Sura Pappa.[73]

Most volumes have been translated into Latin and Ancient Greek, with accompanying teachers' guides, as a way of teaching these ancient languages.

English translation

[edit]Before Asterix became famous, translations of some strips were published in British comics including Valiant, Ranger, and Look & Learn, under names Little Fred and Big Ed[75] and Beric the Bold, set in Roman-occupied Britain. These were included in an exhibition on Goscinny's life and career, and Asterix, in London's Jewish Museum in 2018.[76][77]

In 1970, William Morrow and Company published English translations in hardback of three Asterix albums for the American market. These were Asterix the Gaul, Asterix and Cleopatra and Asterix the Legionary. Lawrence Hughes in a letter to The New York Times stated, "Sales were modest, with the third title selling half the number of the first. I was publisher at the time, and Bill Cosby tried to buy film and television rights. When that fell through, we gave up the series."[78]

The first 33 Asterix albums were translated into English by Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge (including the three volumes reprinted by William Morrow),[79] who were widely praised for maintaining the spirit and humour of the original French versions. Hockridge died in 2013, so Bell translated books 34 to 36 by herself, before retiring in 2016 for health reasons. She died in 2018.[80] Adriana Hunter became translator.

US publisher Papercutz in December 2019 announced it would begin publishing "all-new more American translations" of the Asterix books, starting on 19 May 2020.[81] The launch was postponed to 15 July 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.[82] The new translator is Joe Johnson, a professor of French and Spanish at Clayton State University.[83]

Adaptations

[edit]The series has been adapted into various media. There are 18 films, 15 board games, 40 video games, and 1 theme park.

Films

[edit]- Deux Romains en Gaule, 1967 black and white television film, mixed media, live-action with Asterix and Obelix animated. Released on DVD in 2002.

- Asterix the Gaul, 1967, animated, based on the album Asterix the Gaul.

- Asterix and the Golden Sickle, 1967, animated, based upon the album Asterix and the Golden Sickle, incomplete and never released.

- Asterix and Cleopatra, 1968, animated, based on the album Asterix and Cleopatra.

- The Dogmatix Movie, 1973, animated, a unique story based on Dogmatix and his animal friends, Albert Uderzo created a comic version (consisting of eight comics, as the film is a combination of 8 different stories) of the never-released movie in 2003.

- The Twelve Tasks of Asterix, 1976, animated, a unique story not based on an existing comic.

- Asterix Versus Caesar, 1985, animated, based on both Asterix the Legionary and Asterix the Gladiator.

- Asterix in Britain, 1986, animated, based upon the album Asterix in Britain.

- Asterix and the Big Fight, 1989, animated, based on both Asterix and the Big Fight and Asterix and the Soothsayer.

- Asterix Conquers America, 1994, animated, loosely based upon the album Asterix and the Great Crossing.

- Asterix and Obelix vs. Caesar, 1999, live-action, based primarily upon Asterix the Gaul, Asterix and the Soothsayer, Asterix and the Goths, Asterix the Legionary, and Asterix the Gladiator.

- Asterix & Obelix: Mission Cleopatra, 2002, live-action, based upon the album Asterix and Cleopatra.

- Asterix and Obelix in Spain, 2004, live-action, based upon the album Asterix in Spain, incomplete and never released because of disagreement with the team behind the movie and the creator of the comics.

- Asterix and the Vikings, 2006, animated, loosely based upon the album Asterix and the Normans.

- Asterix at the Olympic Games, 2008, live-action, loosely based upon the album Asterix at the Olympic Games.[71][84][85]

- Asterix and Obelix: God Save Britannia, 2012, live-action, loosely based upon the album Asterix in Britain and Asterix and the Normans.

- Asterix: The Mansions of the Gods, 2014, animated, based upon the album The Mansions of the Gods and is the first animated Asterix movie in stereoscopic 3D.

- Asterix: The Secret of the Magic Potion, 2018, animated, original story.

- Asterix & Obelix: The Middle Kingdom, 2023, live-action, original story

Television series

[edit]On 17 November 2018, a 52 eleven-minute episode animated series featuring Dogmatix (Idéfix in the French version) was announced to be in production by Studio 58 and Futurikon for broadcast on France Télévisions in 2020.[86] On 21 December 2020, it was confirmed that Dogmatix and the Indomitables had been pushed back to fall 2021, with o2o Studio producing the animation.[87][88] The show is distributed globally by LS Distribution.[89] The series premiered on the Okoo streaming service on 2 July before beginning its linear broadcast on France 4 on 28 August 2021.[90]

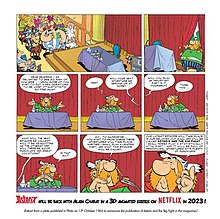

On 3 March 2021, it was announced that Asterix the Gaul is to star in a new Netflix animated series directed by Alain Chabat. The series will be adapted from one of the classic volumes, Asterix and the Big Fight, where the Romans, after being constantly embarrassed by Asterix and his village cohorts, organize a brawl between rival Gaulish chiefs and try to fix the result by kidnapping a druid along with his much-needed magic potion.[91] The series, originally scheduled for 2023,[92][93] will debut in 2025, and will be CG-animated.[94]

Games

[edit]Many gamebooks, board games and video games are based upon the Asterix series. In particular, many video games were released by various computer game publishers.

Theme park

[edit]Parc Astérix, a theme park 22 miles north of Paris, based upon the series, was opened in 1989. It is one of the most visited sites in France, with around 2.3 million visitors per year.

In popular culture

[edit]

- The first French satellite, which was launched in 1965, was named Astérix-1 in honour of Asterix.[95] Asteroids 29401 Asterix and 29402 Obelix were also named in honour of the characters. Coincidentally, the word Asterix/Asterisk originates from the Greek for Little Star.

- During the campaign for Paris to host the 1992 Summer Olympics in 1986, Asterix appeared in many posters over the Eiffel Tower, later it was lost to Barcelona and the 2024 Summer Olympics held 32 years later in the same city after Tokyo in 2021.

- The French company Belin introduced a series of Asterix crisps shaped in the forms of Roman shields, gourds, wild boar, and bones.

- In the UK in 1995, Asterix coins were presented free in every Ferrero Nutella jars.

- In 1991, Asterix and Obelix appeared on the cover of Time for a special edition about France, art directed by Mirko Ilić. In a 2009 issue of the same magazine, Asterix is described as being seen by some as a symbol for France's independence and defiance of globalisation.[96] Despite this, Asterix has made several promotional appearances for fast food chain McDonald's, including one advertisement which featured members of the village enjoying the traditional story-ending feast at a McDonald's restaurant.[97]

- Version 4.0 of the operating system OpenBSD features a parody of an Asterix story.[98]

- Action Comics Issue #579, published by DC Comics in 1986, written by Lofficier and Illustrated by Keith Giffen, featured a homage to Asterix where Superman and Jimmy Olsen are drawn back in time to a small village of indomitable Gauls.

- In 2005, the Mirror World Asterix exhibition was held in Brussels. The Belgian post office also released a set of stamps to coincide with the exhibition.[99] A book was released to coincide with the exhibition, containing sections in French, Dutch and English.[100]

- On 29 October 2009, the Google homepage of a great number of countries displayed a logo (called Google Doodle) commemorating the 50th anniversary of Asterix.[101]

- Although they have since changed, the #2 and #3 heralds in the Society for Creative Anachronism's Kingdom of Ansteorra were the Asterisk and Obelisk Heralds.[102]

- Asterix and Obelix were the official mascots of the 2017 IIHF World Championships, jointly hosted by France and Germany.

- In 2019, France issued a commemorative €2 coin to celebrate the 60th anniversary of Asterix.[103]

- The Royal Canadian Navy has a supply vessel named MV Asterix. A second Resolve-Class ship, to have been named MV Obelix, was cancelled.[104]

- Asterix, Obelix and Vitalstatistix appear in Larry Gonick's The Cartoon History of the Universe volume 2, especially in the depiction of the Gallic invasion of Italy (390 – 387 BCE). In the final panel of that sequence, as they trudge off into the sunset, Obelix says "Come on, Asterix! Let's get our own comic book."

See also

[edit]- List of Asterix characters

- Bande dessinée

- English translations of Asterix

- List of Asterix games

- List of Asterix volumes

- Kajko i Kokosz

- Potion

- Roman Gaul, after Julius Caesar's conquest of 58–51 BC that consisted of five provinces

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico

References

[edit]- ^ "The Asterix Phenomenon – Asterix and the White Iris". Archived from the original on 10 May 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ "Richie's World: The World of Asterix". Angelfire. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Mackay, Neil (29 March 2020). "Neil MacKay's big read: Life lessons from Asterix to bring joy into your life". The Herald. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020.

- ^ Cendrowicz, Leo (19 November 2009). "Asterix at 50: The Comic Hero Conquers the World". Time. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ a b Abbatescianni, Davide. "At Cartoon Next, Céleste Surugue shares the secrets behind Asterix's success story". Cineuropa. Archived from the original on 20 April 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ volumes-sold (8 October 2009). "Asterix the Gaul rises sky high". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 October 2009. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ^ Sonal Panse. "Goscinny and Uderzo". Buzzle.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Luminais Musée des beaux-arts. Dominique Dussol: Evariste Vital. 2002. p. 32.

- ^ "René Goscinny". Comic creator. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ BDoubliées. "Pilote année 1959" (in French). Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2007.

- ^ a b c Kessler, Peter (2 November 1995). Asterix Complete Guide (First ed.). Hodder Children's Books. ISBN 978-0-340-65346-3.

- ^ a b Hugh Schofield (22 October 2009). "Should Asterix hang up his sword ?". London: BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ^ Lezard, Nicholas (16 January 2009). "Asterix has sold out to the Empire". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Shirbon, Estelle (14 January 2009). "Asterix battles new Romans in publishing dispute". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 May 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ "Divisions emerge in Asterix camp". London: BBC News. 15 January 2009. Archived from the original on 19 January 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ "Anne Goscinny: "Astérix a eu déjà eu deux vies, du vivant de mon père et après. Pourquoi pas une troisième?"" (in French). Bodoï. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009.

- ^ "Asterix attraction coming to the UK". BBC News. 12 October 2011. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Rich Johnston (15 October 2012). "Didier Conrad Is The New Artist For Asterix". Bleeding Cool. Avatar Press. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ AFP (10 October 2012). "Astérix change encore de dessinateur" [Asterix switches drawing artist again]. lefigaro.fr (in French). Le Figaro. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "Asterix creator comes out of retirement to declare 'Moi aussi je suis un Charlie'". The Independent. 9 January 2015. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ "La collection des albums d'Astérix le Gaulois" [The collection of Asterix series albums] (in French). 15 October 2018. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Kessler, Peter (1997). The Complete Guide to Asterix (The Adventures of Asterix and Obelix). Distribooks Inc. ISBN 978-0-340-65346-3.

- ^ "Astérix le Gaulois" (in French). 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018.

- ^ "La Serpe d'Or" (in French). 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Astérix et les Goths" (in French). 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Astérix Gladiateur" (in French). 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Le Tour de Gaule d'Astérix" (in French). 26 November 2018. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Astérix et Cléopâtre" (in French). 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Le Combat des chefs" (in French). 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Astérix chez les Bretons" (in French). 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Astérix et les Normands" (in French). 26 November 2018. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Astérix légionnaire" (in French). 26 November 2018. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Le Bouclier arverne" (in French). 27 November 2018. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Astérix aux jeux Olympiques" (in French). 27 November 2018. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Astérix et le chaudron" (in French). 26 November 2018. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Astérix en Hispanie" (in French). 26 November 2018. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018.

- ^ "La Zizanie" (in French). 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Astérix chez les Helvètes" (in French). 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Le Domaine des dieux". Astérix (in French). 23 September 2018. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020.

- ^ "Les Lauriers de César" (in French). 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Le Devin" (in French). 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Astérix en Corse" (in French). 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Le Cadeau de César" (in French). 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ^ "La Grande Traversée" (in French). 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Obélix et Compagnie" (in French). 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Astérix chez les Belges" (in French). 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Le Grand Fossé" (in French). 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ^ "L'Odyssée d'Astérix". Astérix (in French). 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Le Fils d'Astérix" (in French). 27 November 2018. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Astérix chez Rahãzade" (in French). 27 November 2018. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018.

- ^ "La Rose et le glaive" (in French). 27 November 2018. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018.

- ^ "La Galère d'Obélix" (in French). 27 November 2018. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Astérix et Latraviata" (in French). 27 November 2018. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Astérix et la rentrée gauloise" (in French). 27 November 2018. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Le Ciel lui tombe sur la tête" (in French). 27 November 2018. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018.

- ^ "October 2009 Is Asterix's 50th Birthday". Teenlibrarian.co.uk. 9 October 2009. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ "L'Anniversaire d'Astérix & Obélix – Le Livre d'Or" (in French). 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Astérix chez les Pictes" (in French). 26 November 2018. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Le Papyrus de César" (in French). 26 November 2018. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Astérix et la Transitalique" (in French). 24 November 2018. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018.

- ^ "La Fille de Vercingétorix" (in French). 26 October 2019. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019.

- ^ "Astérix et le Griffon" (in French). 29 March 2021. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021.

- ^ "L'Iris blanc" (in French). 30 May 2023. Archived from the original on 30 May 2023.

- ^ "The Twelve Tasks of Asterix is back in a very special anniversary edition". 28 September 2016. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018.

- ^ "Les albums hors collection – Astérix et ses Amis – Hommage à Albert Uderzo". Asterix.com. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ "Erquy: a day in the real-life Gaulish village of Astérix". Yahoo! News. 16 August 2020. Archived from the original on 30 May 2023.

- ^ "The vital statistics of Asterix". London: BBC News. 18 October 2007. Archived from the original on 8 February 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ Embleton, Sheila (1 January 1991). "Names and Their Substitutes: Onomastic Observations on Astérix and Its Translations1". Target. International Journal of Translation Studies. 3 (2): 175–206. doi:10.1075/target.3.2.04emb. ISSN 0924-1884. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ "A to Z of Asterix: Getafix". Asterix the official website. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ "In praise of... Asterix". The Guardian. 2 November 2009. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013.

- ^ a b c "Asterix around the World". asterix-obelix-nl.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ "Accueil – Astérix – le site officiel". Archived from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Translations". Asterix.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ "List of Asterix comics published in Greece by Mamouth Comix" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 9 April 2009. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- ^ "Astérix le Breton: Little Fred & Big Ed (part 1)". ComicOrama en Français. 21 April 2015. Archived from the original on 1 June 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Mark Brown (11 May 2018). "The Ancient Brit with Bags of Grit? How anglicised Asterix came to UK". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ "Astérix in Britain: The Life and Work of René Goscinny". The Jewish Museum London. 10 May 2018. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ "Opinion | Asterix in America (Published 1996)". The New York Times. 24 October 1996. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023.

- ^ Library of Congress catalog record for first William Morrow volume. W. Morrow. 9 May 1970. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Flood, Alison (18 October 2018). "Anthea Bell, 'magnificent' translator of Asterix and Kafka, dies aged 82". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ Nellis, Spenser (4 December 2019). "Papercutz takes over Asterix Publishing in the Americas!". Papercutz. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (23 March 2020). "American Publication of Asterix Delayed Two Months". BleedingCool.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (12 May 2020). "Papercutz Brings Beloved 'Asterix' Comics to US This Summer". Animation Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ "Astérix & Obélix: Mission Cléopâtre". Soundtrack collectors. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "Astérix aux jeux olympiques". IMD. 2008. Archived from the original on 4 February 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Quenet, Marie (17 November 2018). "EXCLUSIF. Une série va raconter la vie d'Idéfix avant sa rencontre avec Obélix". Le Journal du Dimanche (in French). Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ "Dogmatix And the Indomitables: the first spin-off animated TV show based upon the universe of Asterix!". Éditions Albert René. 21 December 2020. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Dogmatix And the Indomitables: the first spin-off animated TV show based upon the universe of Asterix!" (in French). Éditions Albert René. 21 December 2020. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (6 January 2021). "LS Distribution & Studio 58 Unleash Asterix Spinoff 'Idefix and the Indomitables'". Animation Magazine. Archived from the original on 7 October 2024. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ Chuc, Nathalie (24 June 2021). "Idéfix a sa propre série, bientôt sur France 4". Le Figaro (in French). Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ Ellioty, Dave (3 March 2021). "Netflix Orders First Ever 'Asterix' Animated Series". geektown. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Jones, Tony (3 March 2021). "Asterix comes to Netflix in 2023 in an Alain Chabat directed series". cultbox. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Ft, Ma (3 March 2021). "Asterix, Obelix and Dogmatix are Coming to Netflix in 2023". New on Netflix. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (4 February 2022). "French Studio TAT Tapped for Netflix 'Asterix' Series". Animation Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Marcus, Immanuel (9 October 2019). "Asterix: The European Comic Character with a Personality". The Berlin Spectator. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ Cendrowicz, Leo (21 October 2009). "Asterix at 50: The Comic Hero Conquers the World". TIME. Archived from the original on 24 October 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ^ "Asterix the Gaul seen feasting at McDonald's restaurant". meeja.com.au. 19 August 2010. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ "OpenBSD 4.0 homepage". Openbsd.org. 1 November 2006. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ "bpost -". archive.ph. 19 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013.

- ^ "The Mirror World exhibition official site". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ "Asterix's anniversary". Google. 29 October 2009. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "KINGDOM OF ANSTEORRA ADMINISTRATIVE HANDBOOK FOR THE COLLEGE OF HERALDS" (PDF). July 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Starck, Jeff (25 June 2019). "France issues €2 of cartoon figure Asterix". Coin World. Archived from the original on 6 October 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ "The Resolve-Class naval support ship Asterix". 8 December 2017. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

Sources

[edit]- Astérix publications in Pilote Archived 25 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine BDoubliées (in French)

- Astérix albums Archived 11 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine Bedetheque (in French)

Further reading

[edit]- Gabilliet, Jean-Paul (28 March 2013). "A Disappointing Crossing: The North American Reception of Asterix and Tintin". In Daniel Stein; Shane Denson; Christina Meyer (eds.). Transnational Perspectives on Graphic Narratives: Comics at the Crossroads. A&C Black. ISBN 9781441185235. – This is Chapter #16, in Part III: Translations, Transformations, Migrations

- Tosina Fernández, Luis J. "Creatividad paremiológica en las traducciones al castellano de Astérix". Proverbium vol. 38, 2021, pp. 361–376. Proverbiium PDF

- Tosina Fernández, Luis J. "Paremiological Creativity and Visual Representation of Proverbs: An Analysis of the Use of Proverbs in the Adventures of Asterix the Gaul". Proceedings of the Fourteenth Interdisciplinary Colloquium on Proverbs, 2 to 8 November 2020, at Tavira, Portugal, edited by Rui J.B. Soares and Outi Lauhakangas, Tavira: Tipografia Tavirense, 2021, pp. 256–277.

External links

[edit]- Official site

- Asterix the Gaul at Don Markstein's Toonopedia, from the original on 6 April 2012.

- Asterix around the World – The many languages

- Alea Jacta Est (Asterix for grown-ups) Each Asterix book is examined in detail

- Les allusions culturelles dans Astérix – Cultural allusions (in French)

- The Asterix Annotations – album-by-album explanations of all the historical references and obscure in-jokes

- Asterix

- Bandes dessinées

- French comic strips

- Pilote titles

- Dargaud titles

- Alternate history comics

- Lagardère SCA franchises

- Satirical comics

- Comic franchises

- Fantasy comics

- Historical comics

- Humor comics

- Pirate comics

- 1959 comics debuts

- Fiction set in Roman Gaul

- Comics set in ancient Rome

- Comics set in France

- Comics set in Brittany

- Comics set in the 1st century BC

- French comics adapted into films

- Comics adapted into animated films

- Comics adapted into animated series

- Comics adapted into video games

- 1959 establishments in France

- Works about rebels

- Works about rebellions

- Fiction about rebellions

- Gallia Lugdunensis

- Comics by Albert Uderzo

- Armorica